In the summer of 1963, Bang & Olufsen began the development of the first colour television, with engineer Bent Moller Pedersen and an apprentice. Testing the new receivers was still a problem, because there were not many places where colour test cards could be received. It came as a relief to the technicians when, in 1966, Hamburg began to broadcast test cards.

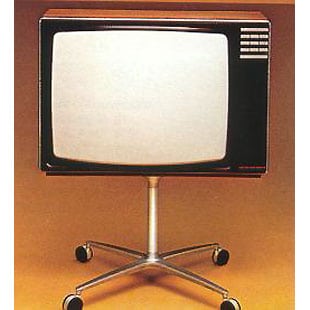

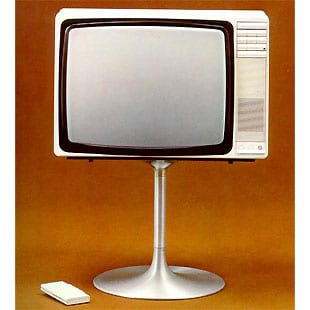

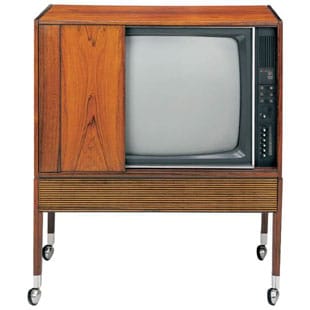

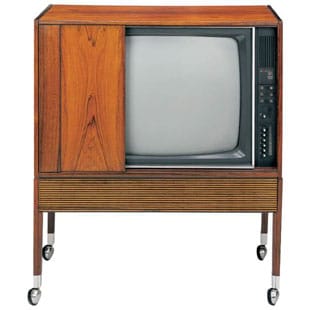

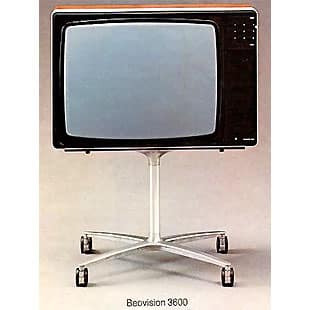

A Bang & Olufsen colour television laboratory with three technicians was set up for a week at a pub 25 km north of Hamburg! In 1967, Bang & Olufsen began producing colour televisions – not without a certain cautious scepticism. Director Jens Christian Sonderup wrote to retailers in the summer of 1967: “At the moment, no one can say with any degree of certainty how sales of colour televisions will develop. Let us be clear about one thing, though: colour television will not be the bread and butter of the sector during the coming season… We must all hope and believe that the radio sector will prove to be a match for colour TV. in B&O circles, let us as usual err on the side of healthy development.” Weighing in at 52 kg, the Beovision 3000 Colour S.1 was an investment for the company in a market that was still feeling its way between different international standards.

The introduction of colour television brought with it some new concepts that were unknown in the days of black-and white reception: colour saturation and colour tone. The picture tube was now 63cm, but it could not be manufactured with sufficient perfection and accuracy for the three electron guns in the picture tube to line up properly on the interior of the picture tube. It was therefore necessary to make some manual adjustments (convergence adjustments) in production as well as in subsequent servicing. The set had to be adjusted at regular intervals. That had also been taken into consideration in this unit. Chief Engineer Knud Hoist and Engineer Bent Moller Pedersen wrote the following instructions with the service technicians (rather playfully) in mind: “Here is B&O’s unconventional solution on the deployment of the convergence buttons. Remove the small panel at the front of the set by lifting it with a coin. The flap can then be pushed far back enough to allow easy access to the convergence buttons while, at the same time, their effect can be seen by looking at the screen. One reason why we have done this is in order not to impose a requirement for future colour TV technicians to be born with extra-long arms!

Despite the director’s cautious scepticism, Chief Engineer Knud Hoist had no doubt that colour television was the way ahead. Speaking in a radio lecture, he said: “If we don’t open the front door to colour television by introducing a Danish colour TV, it will come in by the back door as foreign broadcasts over our borders. Continuing to exclude colour television for much longer from parts of the country that are not covered by Germany will create such a great demand backlog that both the manufacturing sector and the retail sector will both find it difficult to cope when it is finally released. It would be much more desirable to accept what is otherwise an inevitable, slow penetration of colour television into Denmark – and to act accordingly.”

(Taken from Beolink Magazine: ‘The First 50 Years of Television’ © Bang & Olufsen a/s 2002)

” Its 625-line only circuitry initially made it of limited use, as BBC1 and ITV were not widely receivable on this standard, leaving BBC2 as the only viewable programme. Beovision 3000 made up for this though by offering the best quality colour picture yet seen, so good in fact that in certain areas it remained unsurpassed for years after it was withdrawn. When B&O released its first solid state colour sets in 1974, these had to be modified in the field, as their contrast levels seemed ‘washed out’ compared to the then 6 year old 3000s!

Quality was achieved at the cost of considerable complexity. It is well known that cost was not a factor in the design of the 3000, and so any extra parts or stages that could possibly up the performance were added without question. The result was a set with 18 valves, 53 transistors and 48 diodes arranged on two massive chassis. Technical highlights included decoder circuitry working at high voltage to improve colour linearity, DC controlled static convergence, apparently less susceptible to mains voltage variations, separate line scan output stage and EHT generator employing two transformers and two sets of large valves, which improved geometry and dimensional stability, an electronic EHT stabiliser which helped to ensure uniform focusing, and of course, a comprehensive audio amplifier employing three transistors, one valve and heavy negative feedback, all driving a high quality loudspeaker.

These sets demonstrated to the new British market that B&O’s televisions were every bit as good as their audio, and started a long line of development which can be directly traced to the current models. “