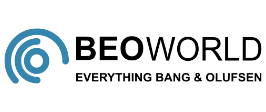

BeoVision 7702

“As yet, none of us need 32 TV channels, let alone 100. But satellite re-broadcasting systems and cable TV, including regional and community networks, might soon change that” (1983 catalogue)

Therefore, Bang & Olufsen equipped all the luxury Beovision models with an advanced digital tuner that had the capacity for receiving 100 UHF channels, 32 of which could be stored in the set’s microcomputer memory for instant recall at the touch of a button.

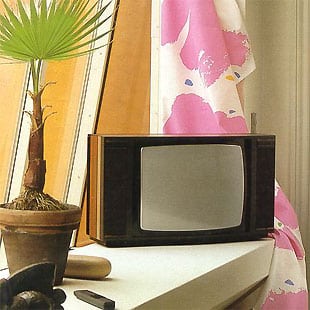

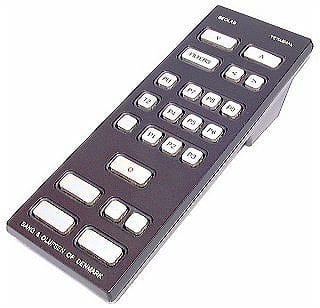

The real boon for most viewers is that you could locate, store and recall any of these stations without leaving your armchair. All you had to do was touch a key on the Beovision Video terminal. So although B&O gave its “future-safe” luxury TV range more micro-electronics, more features and more connection possibilities than ever before, they made, at the same time, all the complex technology even more accessible – instantly. To borrow a phrase from the computer industry, Bang & Olufsen’s ’02-Series’ TVs were “user-friendly”.

Beovisions 5502, 7702, 8802 and 9002 all shared the same advanced chassis design and offered the same user-benefits. They were true “luxury” sets because many ‘extras’ offered by other companies, were given as standard by Bang & Olufsen.

The Beovision Video Terminal supplied with Beovisions 5502, 7702, 8802 and 9002 offered a plethora of operational benefits. In addition there was also an advanced ‘tune and store’ function that allowed you to operate the automatic tuning system from the comfort of your chair.

One touch of the ‘tune’ button started the digital tuner scanning the wavelengths of the UHF band. When it found a station, it stopped – giving you the opportunity to either reject or accept it. If it was an unsatisfactory reception from a distant transmitter (or simply a station you don’t like!), you just pressed ‘tune’ again to continue the search. When you found a station you enjoy, on a channel giving a good, clear reception, you could instruct the set’s microcomputer to remember that transmission frequency by pressing ‘store’ followed by your own choice of pre-set programme number (e.g. for BBC2 you might designate pre-set number 2). Thereafter, whenever you wanted to watch BBC2, you simply touch button ‘2’ on your remote Terminal.

Up to 32 different TV stations could be located and stored in this way, so your Beovision really is ‘future-safe’ because it has plenty of spare capacity to accommodate new programme sources as and when they come ‘on stream’.

The latest type of Beovision Video Terminal also had a button marked ‘sound’. This was only effective with Bang & Olufsen stereo TVs – Beovision 7802 and Beovision 8902.

Beovision 5502 had a 50cm screen and measured 62cm wide, 40cm high (71.5cm including stand) and 39cm deep.

Beovision 7702 had a 22″ screen. Dimensions were 67.5cm wide, 43.5cm high ( 76cm including stand) and 41.5cm deep.

Beovision 8802 had a 26″ screen and measured 77cm wide, 49cm high (80cm including stand) and 45.5cm deep.

All three models had slim cabinets finished in a choice of natural teak or rosewood. White finish was available to special order.